| |

I./2.5.: Nodular prostatic hyperplasia

|

|

Nodular hypertrophy (nodular hyperplasia or benign protatic hyperplasia, BPH) is the most frequent disorder of the prostatic gland, which causes symptoms and is not rarely tumour-like. It hardly ever occurs before 50 years of age, and the disease increases in incidence with age. According to data based on autopsies above 80 years 80-90% of men are affected. It is interesting to note that the condition is quite rare in the Far East. Also interesting that prostatic hyperplasia occurs more often in obese, pyknic-typed men. In adults the prostate normally weighs about 20 gm; its weigh hardly ever exceeds 200 gm even in hyperplasia.

The effect dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a testosteron metabolite has on prostatic tissue is considered to be the most likely reason of hyperplasia. In the prostatic gland DHT is synthesized from the circulating testosteron by the 2nd type of the 5α-reductase present in stromal cells. Both in stromal cells and in epithelial cells the DHT binds to the androgen receptors, stimulating their activity and proliferation with the binding. The testosteron also binds to androgen receptors, but DHT is ten times more efficient, since it dissociates from the receptors more slowly. With the inhibition of the above mentioned receptor in some of the cases the quantity of DHT and with it also the size of the prostate can be reduced. It is likely however, that besides DHT other factors also play a role in the development of a hyperplasia.

Evidence shows that during male climax the ratios of sexual hormones change. In men testicles produce most of the androgen, but it is also produced by the suprarenal glands, and together they also have an effect on the oestrogen level. With age the androgen level reduces, which leads to the relative predominance of oestrogen level. Based on all this, the most likely combination is that with age Sertoli-cells produce relatively more oestrogen, while interstitial Leydig-cells produce less androgen. Oestrogen likely raises the number of androgen receptors, therefore sensitizing the cells to DHT. Besides the above mentioned ones other hormonal combinations and not hormonal stimuli (also endogenous and exogenous) can affect the prostate, which can cause hyperplasia independent from the hormonal system.

|

|

Whatever the reason is, it is a general observation that the hyperplastic changes of the prostate start around the age of 40, reach their maximum around 60 years of age and after that stagnation or a minimal growth occur only. The anatomical localization of the gland makes the symptoms especially understandable. Hyperplasia develops in the inner, periurethral zone of the prostate (while carcinomas occur rather in the outer, peripheric glandular tissue and can be palpable during a rectal digital examination as an area firm as cartilage), so it is understandable the especially problems related to urine discharge occur. With a rectal digital examination the enlarged prostate is relatively soft, elastic and nodular. This nodular structure can also be observed macroscopically and on the cut surface as well. The look of the cut surface also depends on which tissue of the gland is affected by the hyperplasia.

If hyperplasia affects mainly the glands (adenomatous hyperplasia), then noduli of different size can be seen. The noduli are well defined and are surrounded by pearl-coloured fibromuscular connective tissue. Sometimes at the same time cystic areas can be observed as well, filled with an opalescent excretion. Corpora amylacea (ovoid laminated protien concretes in the glands) and prostatic stones are not rare. If the hyperplasia is primarily fibromuscular, then the cut surface is homogenous, glazy, sometimes spongeous and the growing nodule compresses the surrounding tissue, which forms a pseudocapsule around the nodule. Histologically multicentric aglandular fibromuscular nodules (so-called Endes-nodules) form, which stimulate the surrounding glands. The cumulating epithelial elements spread into the fibromuscular nodules, resulting in the typical biphasic nodules containing both stroma and glands.

The number of acini also increases, many of them dilates or invaginates and forms villous outgrowths. The cumulated adenous structures are partially lined by active cylindrical epithelium, partially by inactive, flattened cells. Lymphocytic infiltration can often be observed in the connective tissue as a concomitant phenomenon (4th microphoto). Depending on the ratio of stromal and glandular components, mainly stromal or mainly glandular nodules can also be present, and naturally varying combinations can also occur (fibrous or fibrovascular nodule, fibromuscular nodule, muscular nodule, fibroadenomatous nodule, fibromyoadenomatous nodule, and glandular adenomatous nodule). In case of a prostate hyperplasia, infarction can also occur, since the nutrition of the nodules arrives from the periphery and as the nodules grow, they compress the peripheral vessels, which leads to ischaemia and necrosis.

|

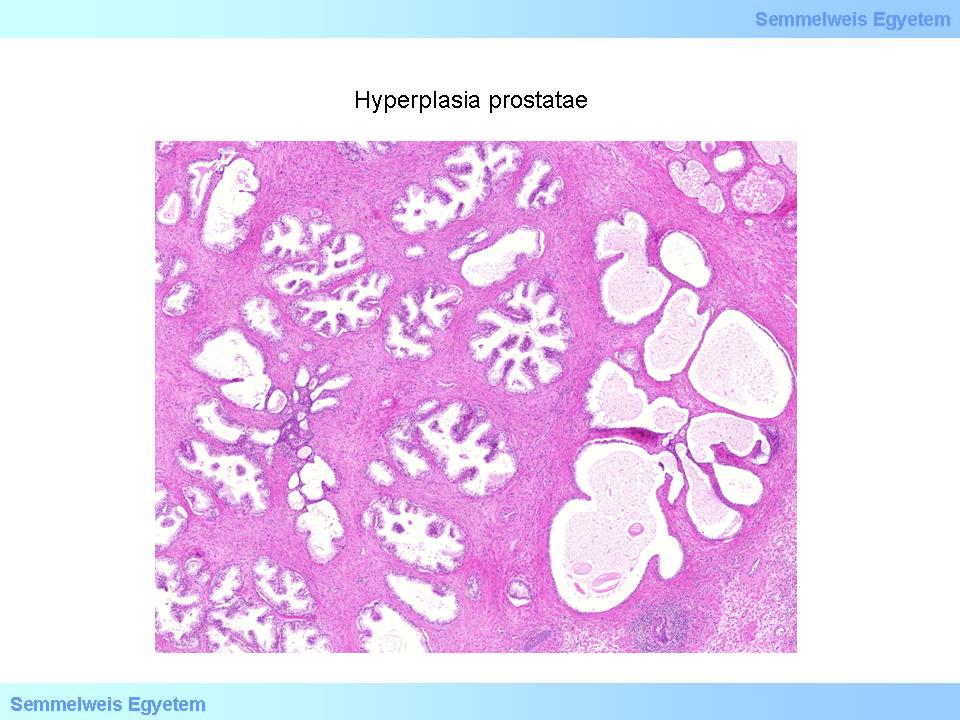

Look at the picture and analyze it!

|

4th macropicture: Prostate hyperplasia. In the fibromuscular stoma containing nodular chronic inflammatory infiltrations several, mostly hyperplastic, but sometimes flattened prostate cross-sections in nodular arrangement varying in size and width, lined with two cell lines can be detected.

|

Clinically this can be associated with haematuria, or even urine retention. In the surroundings of the infarcts squamous metaplasia of the glands can occur, which can be accompanied by a nodular inflammatory reaction. Nodular chronic or acute prostatitis (chronic and acute prostatitis) can accompany prostatic hypertrophy without infarction as well. The chronic component develops mainly insterstitially, while acute inflammation is observed in the stagnating discharge within the dilated glands (secretum retention). In these cases the prostatic gland becomes firm and the level of prostatic enzymes (Se-PSA – serume prostate specific antigen) also increases. In clinical practice the major morphological consequence of prostate hyperplasia is urethral stricture, which is presented in functional disturbances of urination: frequent urination (pollakisuria), difficult urination (dysuria), partial or total inability to excrete urine (partial or total urine retention), and painful urination (strangury).

Urine retention is associated with inflammation by time. The muscular wall of the bladder shows a compensatory hypertrophy and because of the continous contractions a typical bundling (trabeculation) occurs. The bladder wall can be twice as thick as in healthy people, diverticula develop, and without treatment the muscle decompensates and the bladder substantially dilates. In its normal position and angle the ureteral orifice has a valve-like function which does not allow for retrograde flow. If the bladder is unable to compensate, it dilates and this function becomes damaged and because of the higher pressure in the bladder a retrograde flow develops. These changes lead to the dilation of the ureter and then to the dilation of the pyelon. Later the renal parenchyma becomes atrophied as well (hydroureter és hydronephrosis). Naturally due to the stagnation an infection occurs as well, which causes pyelonephritis. The damage of the renal parenchyma leads to a renoparenchymal hypertension.

|

|