| |

III./2.3.: Purulent meningitis

III./2.3.1.: Basic forms

|

Recently, and especially in clinical practice, certain cerebral inflammatory processes are referred to as „cerebritis” [16P-Ref16>16R-Ref9]. The purpose of this is to distinguish local, circumferential, purulent-exudative inflammations originating from the meningeal spaces and then infiltrating the brain tissue (cerebritis – 16P-1. macropicture), from diffuse inflammations, mostly with viral etiology, and characterized by lymphocytic infiltration (encephalitis).

|

Despite its protection, the central nervous system might be part of inflammational processes in various ways, affecting various regions. The inflammation can be isolated meningitis – 16P-1. drawing), or combined meningoencephalitis – (1. and 2. micropictures), or possibly meningoencephalomyelitis) too, affecting the meninges, the brain tissue and the spinal cord.

Drawing 1: Developmental phase of purulent meningitis: the exudate is present only in the sulci and only along the middle line of the convexity.

|

Micropictures 1-2: Meningitis infiltrates the brain tissue directly (micropicture 1), and through the perforating vessels (micropicture 2), creating combined meningoencephalitis. Furthermore, on micropicture 1,it can be observed that from the inflammated area the process infiltrates the wall of the vessels, resulting in secondary angitis and consequential thrombosis. (Hematoxylin-eosin; from the digital, educational image-archive of the Semmelweis University, 2nd Department of Pathology)

III./2.3.2.: Meningitis with otogen, orbital, nasal origin

Origin of inflammatory processes infiltrating the braincase might be one of the wholes, cavities of the facial skeleton. Most frequently, purulent meningitis develops from otitis media. Inflammation of the bones of the brain case (osteomyelitis), or inflammatory processes of the scalp (furunculus, carbunculu;, infected, in certain cases ruptured atheroma cutis) can also be points of origin. Infiltration generally goes through venae emissariae, or through diploic veins or their canals (canales diploici) of the vault of the skull.

III./2.3.4.: Meningitis originating from infections through preformed structures

|

|

In these cases, ascending infection takes place without obvious inflammation of the environment, or deformating injury of the local structures, but via the „weak points” (loci minoris resistentiae) of normal anatomic structure. Entry gate may be (a) Batson venous plexus (connecting the the deep pelvic veins to the internal vertebral venous plexuses; (b) the so called Redlich-Obersteiner’s zone (proximal, short part of a nerve, where there is no Schwann-cell myelin yet on the axon) of the dorsal roots of the spinal cord; (c) incomplete closure of the neural tube (dysraphia) due to malformation.

III./2.3.5.: Haematogen meningitis

A septic embolus (or sometimes called mycotic, referring to any type of infection not only mycotic, see also aneurysma mycoticum!) arriving with the blood stream and stucking mainly in the plexus choroideus, or in small, superficial arteries, cause intracranial infection (16P-3. micropicture). In most of the cases,the source of the haematogen infection is pneumonia, bacterial endocarditis, purulent processes in the oral cavity, endometritis purulenta.

|

Look into the pictures!

|

Macropicture 1: Abscessus cerebri. The core infection from which the abscessus develops arrives as an embolus via haematogenic infiltration. If the same picture develops with meningitis in the background, some authors would call it cerebritis in order to indicate the meningeal source of the inflammation. (From the image-archive of the Semmelweis University, 2nd Department of Pathology–collection of Attila Kovács)

|

Micropicture 3.: A septic embolus, stuck in one of the superficial, circumferential vessels , caused the extensive inflammation of the meningeal space. (Hematoxylin-eosin; from the digital, educational image-archive of the Semmelweis University, 2nd Department of Pathology)

|

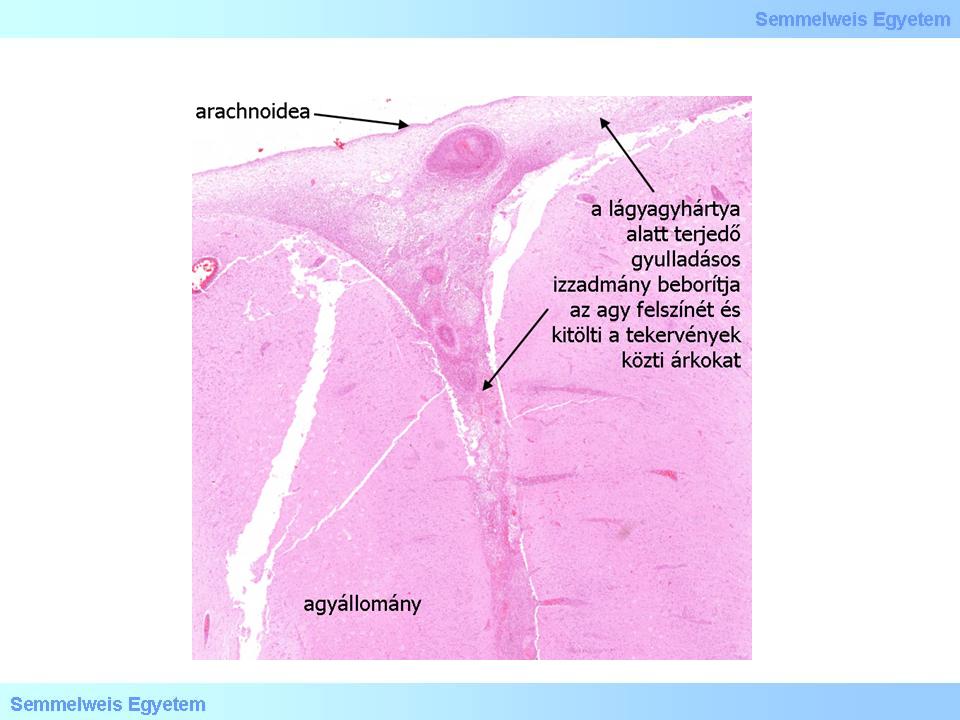

Micropicture 4: Purulent exudate may infiltrate the surface of the brain and fill out sulci. (Hematoxylin-eosin; from the digital, educational image-archive of the Semmelweis University, 2nd Department of Pathology)

|

III./2.3.6.: Meningitis in childhood, and in adulthood

In childhood the cause of acute, purulent meningitis may be:

|

|

-

- Haemophylus influenzae

-

- Meningococcus (Neisseria meningitidis)

In adults:

-

- Streptococcus pneumoniae

-

- Meningococcus (Neisseria meningitidis)

-

- Staphylococci

|

Look into the table!

|

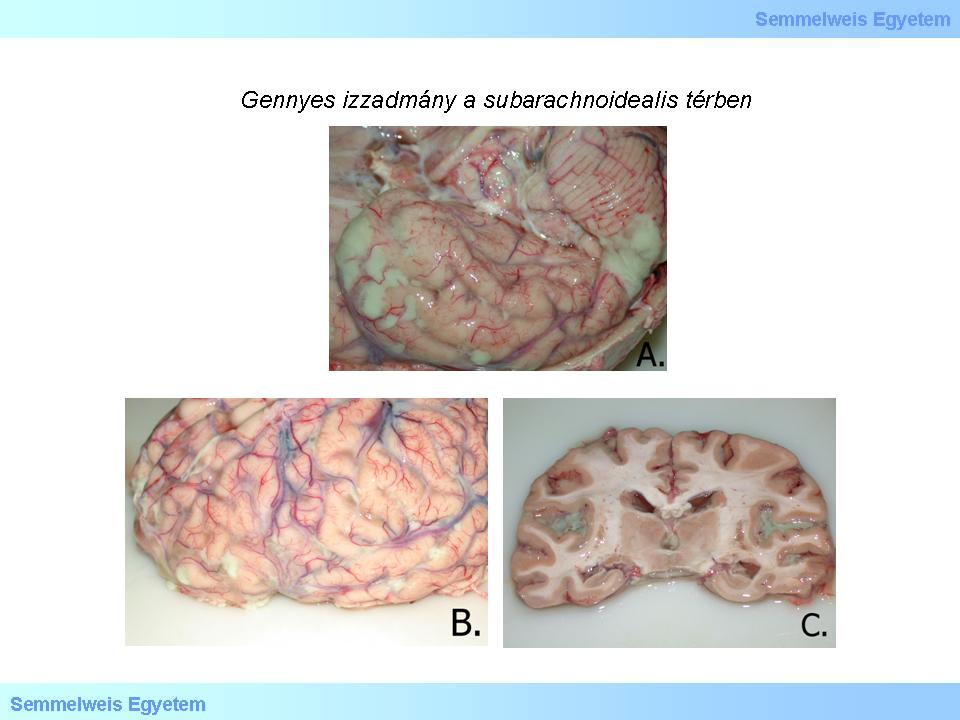

Macropicture 2 A-C: The purulent exudate fills out the subarachnoidal space flared between the sulci, and is present everywhere due to its diffuse extension (From the image-archive of the Semmelweis University, 2nd Department of Pathology–collection of Attila Kovács)

|

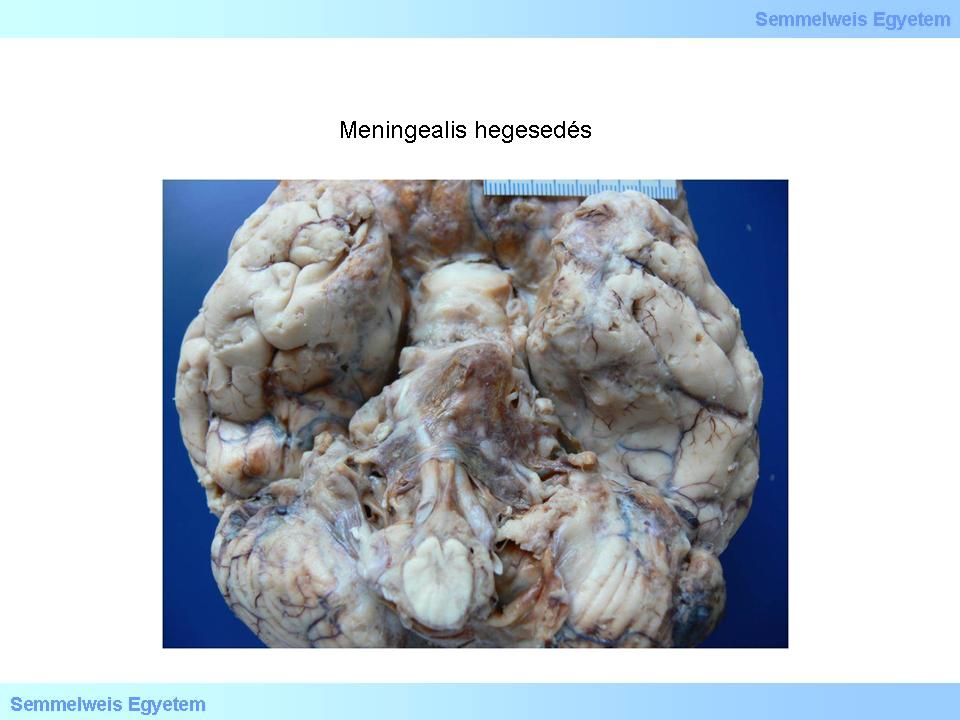

Histologically, neutrophil infiltration (drawings 16P-2A-B.) is followed by mononuclear elements after the first week. Later, over time, lymphos-plasmocellular elements, histiocytes, fibroblasts start to dominate the histopathologic picture. The progressive scarring (Macropicture 16P-3) can be accompanied by hydrocephalus and late epileptic complications in these age groups too. Clinical appearance of purulent meningitis can be characterized by high fever, hardly tolerable headache, vomiting, neck stiffness, and as an important sign: inability to tolerate light (photophobia). Various neurological symptoms may occur: seizures, cranial nerve palsy, functional losses. It is important that meningeal signs (neck stiffness, Kernig-, Brudzinsky- , and Lasègue- signs) might be present in subarachnoideal haemorrhage (SAH) either. It should be noted that degenerative vertebral/joint disease may also be at the background of neck stiffness and pain!

|

Look into the picture!

|

Drawings 2 A-B: The subarachnoidal space in schematic pictures when intact (A.) and under purulent, inflammated (B.) conditions.

|

Macropicture 3: If the exudate of the acute meningitis cannot dissolve, it leads to scarring. (A favor of Péter Molnár; University of Debrecen, Medical and Health Sciences Center, Department of Pathology)

|

An increase in the intracranial pressure is a real and important possibility, and its potentially fatal complications also need to be taken into account. The Meningococcus-infection can be characterized by almost pathognomical maculo-papular exanthems on the skin, which may transform to petechias and purpuras indicating Meningococcal-sepsis already. Septicaemia leads to peripheral collapse of the circulation, to shock, all of which can be worsened by the so called adrenal-apoplexy. This phenomenon is called Waterhouse-Friedrichsen-syndrome that is haemorrhagic adrenal necrosis along with adrenal thrombosis and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC). Latter can even lead to cardiac failure and death, due to the acute loss of steroid hormones (hormonal insufficiency) that are needed in acute stress situations for the body to be able to cope and adapt.

III./2.3.7.: Tuberculous meningitis

|

|

A chronic type of meningitis, in which sometimes it is difficult to macroscopically differentiate the pulpy, caseous, greyish yellow exudate from that in acute, purulent meningitis, especially when the latter is thick and clammy. It develops as part of the post-primary tuberculosis, and it is caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis, similar to other sites of tuberculosis. Exudate is the most expressed on the basal surface of the brain, and in most of the cases, in the basal cisterns, which is referred to as meningitis basilaris.

|

|