| |

III./2.3.: Hydrocele testis and other related malformations

III./2.3.1.: Hydrocele

|

|

Normally the cavity of the tunica vaginalis (between the visceral and parietal layers, which have both a secreting and an absorbing function) contains only a few drops of serous fluid. The accumulation of this fluid is the hydrocele (’fluid hernia’) (1st macrophoto). In case of a congenital hydrocele the processus vaginalis of the peritoneum is open, which can be perceived as a failure of the funicular development to close completely. With the postnatal obliteration of the communication the hydrocele resolves spontaneously. In case of an infantile hydrocele the funiculus closes only partially, but the accumulated fluid does not communicate with the abdominal cavity.

|

Study the pictures!

|

1st illustration:Hydrocele (Kiss Balázs)

|

1st macrophoto: Hydrocele. The fluid accumulated between the testicular layers appears from the outside as tightness.

|

An idiopathic hydrocele is a hydrocele of unknown origin. This condition develops mostly slowly, it is not painful, and it is likely caused by the disturbed adsorbing and excreting function of the testicular layers. An acquired hydrocele

can be caused by congestive heart failure, inflammation (eg. gonorrhoea, syphilis, tuberculosis, testicular and epididymal processes, tumours, testicular surgeries, inguinal hernia operations, testicular torsion, or trauma. In case of a testicular torsion the fast evolving fluid results in an acute hydrocele, which is very painful because of the tightening of the testicular layers (tunica vaginalis). The volume of the fluid is usually between 10-300 ml, but in extreme cases it can be as much as 4-5 litres as well. Its protein content is usually around 6%.

|

|

The otherwise relatively clear fluid can become cloudy in case of overinfections see below). Due to bleedings its colour can change to brownly stained, and with the worsening of the bleeding the hydrocele can even become a haematocele. In the centrifugate of the hydrocele microscopically only a few mesothelial cells and lymphocytes can be observed, other cellular components are not typical, except for inflammatory cells.

The sack of the hydrocele can have one or more compartments (uni- or multilocular hydrokele). Its internal surface is mostly smooth, but sometimes adhesions and fibrous processes or calcifications occur. If the opening of the tunica vaginalis into the abdominal cavity is wide enough then a scrotal hernia can develop. If the fluid propagates within the compartment, which has developed between the layers of the spermatic cord (funiculus spermaticus) it is called a funiculocele.

III./2.3.2.: Hematocele

Hematocele is an effusion of blood in the tunica vaginalis. Slowly developing (spontaneous) hematoceles are rare. The condition can develop due to hemophilia or tumours. Inflammations cause a relatively faster developing hematocele, while hematoceles of sudden onset are almost always of traumatic origin. Naturally, the hematoma can organize (1st micropicture) and become thick, dense. If it exists for a long time, the tunica vaginalis thickens excessively, can become fibrous and partially calcify.

|

Study the picture!

|

1st micropicture: Hematocele. Fresh blood can be observed between the testicular layers. The partial organization of blood refers to the recurrent, prolonged nature of the process.

|

III./2.3.3.: Varicocele

|

|

Varicocele is the elongation, dilation and varicosity of the pampiniform plexus and the veins of the scrotal layers (2nd micropicture). In most cases (90%) varicoceles develop on the left side, apparently due to the difference between draining of the left and right spermatic vein; while on the right side the testicular vein drains at an acute angle into the inferior vena cava, the left testicular vein connects into a side-branch, to the renal vein with a 90-degree angle.

|

Study the picture!

|

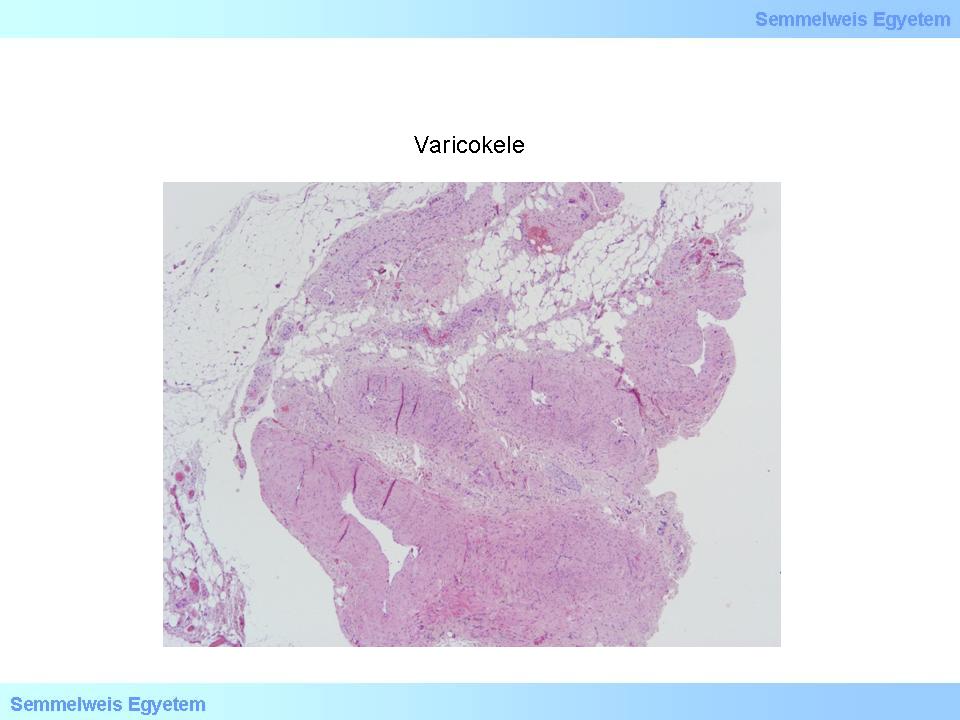

2nd. micropicture: Varicocele. The veins of the pampiniform plexus are dilated, their wall is thickened.

|

Further causes include retroperitoneal space occupying processes, renal cancers, inflammatory infiltrations, postirradiation pelvic scarring. The passive hyperaemia, venous stasis with increased temperature (local hyperthermia) affects the spermatogenesis adversely and the fertility problem becomes irreversible after a longer presence. Histologically the disorganization, atrophy and detachment of the germinal epithelium can be observed. Because of the long lasting development of the process patients usually do not complain of pain, only of an unpleasant inguinal dragging sensation or of pressure in the waist. The dilated veins are palpable. Their swelling usually lowers when lying down.

III./2.3.4.: A ’namesake’: mucocele and its peritoneal complication, the pseudomyxoma peritonei

|

|

Mucoceles do not develop neither in the testicular layers nor in the abdominal cavity directly. They rather occur within cavernous organs layered with mucus producing epithelial cells. The condition is only mentioned here because of its name, so that all different ’-celes’ could be listed after each other. Mucocele is a dilated cavity filled with mucin with one or sometimes more compartments. Its occurrence is not rare e.g. in the appendix, where it can both be of tumorous or of non-tumorous origin. The previous one develops mainly due to obstruction; when a hard mass of faecal matter (coprolith, faecolith), a gall stone, a foreign body, or a coecal tumour ’sitting on’ the access of the appendix, etc. closes the lumen of the appendix, resulting in mucus accumulation in the area behind. The development of mucinous tumours (mucinous adenoma or adenocarcinoma) in the appendix is a more severe problem. Such tumours can also develop in the form of a mucocele. In both cases the appendix can transform into a sac filled with mucus and the danger of rupture appears. The rupture of the sac results in a peritoneal pseudomyxoma, so on the peritoneal surface mucus producing, sometimes even cytologically benign-looking cells settle and with growing they cover its surface. Proper to their biological function they produce litres of mucus, which eventually fills the abdominal cavity almost completely and on the long term (with the organization of the mucous product) leads to intensifying abdominal pain and then to ileus.

III./2.3.5.: Peritonitis

’Independent’ disorders of the peritoneum occur rarely. They develop together with the inflammations and tumours of other organs. Considering the whole peritoneal surface of the abdominal cavity and both genders, peritonitis can originate from many conditions, mostly from bacterial infections, chemical or physical irritations. The inflammation – especially in case of a persistent developmental connection – can spread onto the testicular layers and the overinfection of the primary disorder of the scrotal layers (hydrokele) can cause an inflammation in the peritoneal surface of the tunical vaginalis.

III./2.3.5.1.: Sterile peritonitis

|

|

The condition can be caused by gall or pancreas exudates entering the abdominal cavity and also by surgical interventions (especially certain sterile materials, e.g. talcum, foreign body). Some autoimmune diseases (e.g. SLE) can also lead to peritonitis, similar to pelvic inflammations (salpingitis, oophoritis) or endometriosis.

III./2.3.5.2.: Infected peritonitis (peritonitis infectiosa)

The condition occurs due to bacterial infections. Almost every infectious disorder of the intestinal wall (appendicitis, perforation of any part of the gastrointestinal system, abdominal trauma, etc.) can cause peritonitis. Almost all kinds of bacteria can cause peritonitis, especially E. coli (see below), different Streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococci and Clostridium perfringens, etc. The condition can even develop due to Candida, Actinomyces, and amoebal infections. The gonococcus and the Chlamydia trachomatis can originate from gynaecological diseases. Certain factors (e.g. cirrhosis or impoverished health) can precipitate the occurrence of bacterial infections. In these cases a ’spontaneous peritonitis’ can develop as well (i.e. the infection is of unknown origin).

III./2.3.5.3.: Morphology

|

|

The morphology of peritonitis depends greatly on the causative agent, on the acute or chronic type of development, and of course on illness severity and duration. The first sign of an acute peritonitis is when the normally smooth, glossy, reflecting serous membrane becomes lightless, uneven and fibrinous deposits develop, which can be drifted away. In a more severe form the fibrin builds a coherent membrane, which adheres the intestines together with the abdominal wall, the liver and the spleen and with each other. A growing number of pus cells appear mostly already in this case; this process is indicated by yellow, yellow-green decolouration.

The propagating exudate often accumulates in smaller or bigger cavities. Their encapsulation can result in abscesses, or the exudate is divided slowly into compartments (septation).

Subhepatic and subphrenic abscesses are especially common. The acute inflammation can be dissolved by appropriate treatment applied on time. It is not rare, though, especially if the exudate is extensive, that residual fibrosis and adhesions remain as complications, which can lead to the strangulation of bowels and to ileus.

III./2.3.5.4.: Special forms of peritonitis

|

|

Granulomatous peritonitis can be caused by infectious or non-infectious factors. Tuberculous peritonitis occurs rarely nowadays. The disease manifests as small, millet-sized nodules in its most characteristic form. The infection can be the result of miliary dissemination or it can originate from the abdomino-pelvic region. Granulomatous peritonitis can also be caused by fungi and parasites (e.g. schistosoma, oxyuris, ascaris, etc.).

Granulomatous peritonitis of non-infectious origin is caused by a foreign material (mainly talc or other surgical materials: textile fibres, haemostatic materials, oily contrast materials, etc.). Rarely the condition can be generated by a ruptured dermoid cyst, sometimes by fibrous materials from the bowels, or other components (lanugo, keratin, etc.) entering the abdomen during surgeries, Caesarean sections as well. Reactive peritonitis is characterized by adhesions, which are frequent complications of abdominal surgeries. Sometimes the excessive adhesions are hard to be distinguished from mesotheliomas (see later). Sclerosing peritonitis is a rare, pronounced thickening of the peritoneum. It can be primary, idiopathic, or secondary, developing after peritoneal dialysis, sarcoidosis, etc.

III./2.3.6.: Peritoneal tumour-like lesions and tumours

|

|

The most important peritoneal tumour is the malignant mesothelioma of the tunica vaginalis, which is often accompanied by a hydrocele. In these cases extensive hypertrophy of different extent is present on the visceral and parietal layers. The tumour spreads partially towards the testicles, partially towards the spermatic cord. Metastases occur primarily in the inguinal lymph nodes. It is not rare that in this localization the mesothelioma is the ’forerunner’ of the generalized mesotheliuma of the peritoneum, or sometimes the pleura, but years can pass until they develop. The primary tumours of the peritoneum in a broader sense are rare, metastases are more frequent. Their differentiation can be complicated.

III./2.3.6.1.: Mesothelial hyperplasia

Reactive hyperplasia of mesothelial cells can occur during inflammation, surgical procedures, etc. Solitaire or multiplex nodules are present. The condition can accompany the inflammations, tumours of certain organs as a reactive phenomenon, causing differential diagnostic difficulties. It is often present together with hernias (e.g. inguinal hernia), or in women in case of salpingitis, endometriosis, ovarium tumours. The histological picture can be troublesome, since the mesothelial cells can form a solid, tubular, papillary, or tubulopapillary structure, so their differentiation from mesotheliomas is not easy.

III./2.3.6.2.: Peritoneal cysts

|

|

Peritoneal cysts can most often be observed in women of reproductive age. In most cases a solitaire or multiplex sac with one compartment and a thin, transparent wall can be seen, which is either attached to the peritoneal wall or hangs by a stem in the abdominal cavity. Sometimes it can be as big as 20 centimetres. The multicompartmental form is sometimes called a benign cystic mesothelioma, which is often preceded by abdominal surgeries, pelvic inflammations or endometriosis.

III./2.3.6.3.: Other tumour-like lesions

The calcifying fibrous pseudotumour is a rare lesion, which can be mistaken for peritoneal carcinosis. In most cases it forms a calcifying ’tumour’ with a diameter of 1-2 centimetres. Another similarly rare condition is the splenosis, which can develop from splenic deposits originating from a splenectomy or a splenic rupture.

Several reddish nodules can be observed in the abdominal cavity, which can lead to a misdiagnosis (of endometriosis, vascular tumours, etc.) macroscopically. A tubal pregnancy can lead to the development of trophoblastic implants. Endometriosis can also occur on the peritoneum, in the form of multiple, small, reddish nodules, sometimes showing through the mesothelial lining seen during surgical observations or during laparoscopy.

III./2.3.6.4.: Mesothelioma

|

|

Mesothelioma is the most common primary tumour developing from the mesothelium. It is similar to the mesotheliomas of the pleura and the pericardium. The mature (well-differentiated) papillary mesothelioma is a rare, solitaire or multiplex tumour, which appears in the form of smaller-bigger, whitish nodules. Diffuse malignant mesotheliomas are less frequent on the peritoneum as on the pleura. In some patients the CA-125 level is elevated, often accompanied by ascites. The mesothelioma’s relation to asbestos is emphasized in this localization as well, but chemicals, irradiation and genetic factors also play a role in its development. The peritoneum is partially diffusely thickened, partially with nodules and plaques. Its invasive and metastatic feature is prominent; mainly abdominal organs are affected.

Histologically similarly to pleural mesothelioma tumours of both sarcomatoid and biphasic structures can develop. It can be important to know the immune reactivity of the mesothelioma for the differentiation from other tumours: it is cytokeratin- (especially CK5/6 – epithelial marker), vimentin- (mesenchymal marker) and calretinin-, WT1-, HBME-1 (mesothelial markers) positive; CEA- (carcino-embryonal antigen), CA19-9- (tumourmarker), S-100- (neurogenic marker), BerEp4 (epithelial mucin marker) negative. The combination of more immune markers always leads to a more certain judgement.

III./2.3.6.5.: Metastatic tumours

|

|

Several tumours can spread onto the peritoneum directly, with lymphogenic or haematogenous dissemination. Metastases mainly derive from gastrointestinal and gynaecological tumours, but primary tumours of the lung and the liver also metastasize to the peritoneum (peritoneal carcinosis). Ovarian tumours, tumours of the colon, stomach and pancreas spread onto the peritoneum also very often. Nodules of different size or fluid sometimes stained with blood of varying quantity are present. The carcinosis can be recognized by the tumour cells found in the fluid. If the primary tumour is testicular cancer, it can reach the cavity of the tunica vaginalis by breaking through the scrotal layers, creating a continuously refilling hydrocele, which is stained with blood.

|

|